By Jean Baptiste Ndabananiye

The life of Elisabeth Hagenimana from Rukoma Sector in Kamonyi District in Rwanda’s South is a haunting embodiment of Rwanda’s post-genocide legacy—a child born into the paradox of life, shaped by the heavy burden of her parents’ past. With her father imprisoned for committing genocide against the Tutsi and her mother scarred by the genocide’s horrors as a genocide survivor, Hagenimana grew up navigating the harrowing void between guilt and grief. This article comprises these sections:

- Hagenimana’s life before getting healed

- Her transformation journey

- Responses to questions raised by some of the students

- Breaking the chains of history: a global struggle for unity and healing

Hagenimana’s life before getting healed

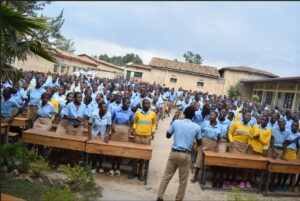

“I have been born to a parent who has notoriously committed the genocide against the Tutsi in our sector. My life has been devastated by being born to a coward parent who has perpetrated the genocide,” she has recently told over 752 students in Ruyanza School Complex in Nyarubaka Sector, Kamonyi District in Rwanda’s South in a peace conference organized by Christian Action for Reconciliation and Social Assistance (CARSA).

“The genocide occurred while I was one year old, meaning that I didn’t witness it firsthand but have learned about it through what others have told me. I have grown up in extremely difficult life. First, I was brought up like an orphan while I had both parents because my father was being jailed.

Furthermore, I was reared under the influence of my mother’s psychological wounds since she belonged to the Tutsi social class so that she was heavily experiencing shock. Consequently, I faced extremely bitter life both on my father’s side and my mother’s.”

Hagenimana’s childhood was a battleground of shame and rejection, where the crime of her father cast an unrelenting shadow over her life. Branded as “the genocide perpetrator’s daughter,” she endured recurrent torment from some teachers. “My father was renowned in our entire sector and moreover I and he resembled each other very closely; which hurt me more.

You who are here, you could immediately say ‘That’s the man’s daughter’, if you knew him. Wherever I arrived, I was shamed by being called a genocide perpetrator’s daughter. I joined secondary education in 2 000, there were teachers who constantly haunted me, repeatedly reminding me that my father had killed during the genocide.”

The crushing weight of inherited guilt that left no corner of her world untouched. “Some people on the side of my father used to tell us ‘You, children of a Tutsi woman who has caused our relatives to be kept in prison’, because their relatives had committed the genocide.

Our relations— with those who have survived on my mother’s side, because of their wounds engendered by the genocide —were also difficult, since we were born to a genocide survivor. Even our mother punishing us as a parent does to their children, sometimes corrected us with her wounds too, telling us ‘You are like your genocide perpetrator father’.”

“At school the issue lay on both sides too. My fellow students stigmatized me. For example, a child whose father was imprisoned for committing the genocide, their mother told them that it was my father who had ordered their father to perpetrate the genocide. As a result, while sitting together, this child attacked me, saying ‘Go away from me, it’s your father who has abetted mine in doing the genocide and he has been kept in prison. While sitting with a child born to parents who have survived the genocide, the issue was the same since they couldn’t even lend me their pen.’”

The weight of this shock once caused her to suspend her education. “Because of this I dropped out of school in the third year, though I returned there afterwards. I lived with the shock for 28 years.”

Her transformation journey

“I am now before you, owing to CARSA which has healed my wounds. Before recovering, I felt that every person viewed me in my father’s image. I hated my father to the ultimate extent that I never visited him in prison till 2017 when he died. Nevertheless, I have asked for pardon for this though he has passed away so that I could not face him and request him for the forgiveness.”

“Finding a person to whom I talked openly about my tragic past constitutes the key which opened the journey. It all started in a study that CARSA was conducting while I was 25 years-old. I think that they were identifying unity and reconciliation-related subjects on which to focus, while educating the youth.”

Hagenimana contends that the interview with her was extremely difficult. “They asked me which among Hutu, Tutsi and Twa do you identify yourself as? Instead of answering, I burst into tears and asked them to stop the interview especially since they’d first told me I held the right to have it suspended.

They came back on the following day and encouraged me to openly disclose my historical background and I did so. I then intensely feared a tall person with a long nose, and I interacted with such a person in the interview. I felt maximally relieved by how one of these people I used to fear then treated me with words filled with conspicuously true love, dignity and serenity.”

While the interaction in the interview created the enabling environment for Hagenimana’s path to get healed, 5-day peace community dialogues and 7-day training completed her transformation. “The dialogues concentrated on the history of the Rwandans, among other key topics. Each dialogue took two hours a day, one hour was dedicated to speeches by adults who addressed us, while another hour was devoted for us to ask questions.

As soon as we ended the dialogues, I rushed to establish a peace club— with CARSA’s intervention— named ‘Abubatsi b’Amahoro Rukoma [ Peace Builders Rukoma] consisting of 40 members including those from parents who have perpetrated the genocide, genocide survivors and those whose parents never engaged in the genocide.”

Amidst the deep scars of a past fraught with unimaginable pain, one powerful moment of recovery broke through the darkness, leaving a lasting impression in Hagenimana. The following words reflect the profound impact of this transformative experience. “The definitive role was played by the training and seeing a genocide perpetrator sitting with a genocide survivor against whom the perpetrator had offended, it really baffled me.

Seeing that a genocide perpetrator is sitting with a survivor whose relatives killed by the perpetrator, while both of them showing us in the dialogue that they had been truly reconciled and exhorting us to wholeheartedly support unity and reconciliation conclusively convinced me. CARSA has become my family. In CARSA you only focus on unity, reconciliation and development; never on Hutu, Tutsi and Twa issues. That’s how I have been healed of the shame and wounds.”

In a journey of profound healing and reconciliation, the following words capture Hagenimana’s powerful commitment to unity and the transformative efforts to rebuild what was broken. “Let’s remember the slogan ‘Our unity is our strength’, I am now resolute in my mission to rebuild the foundation which my father and others have destroyed. We engage in peace clubs and the mothers and the fathers—genocide survivors and perpetrators reconciled— who wiped out tears that I shed in the dialogues optimally galvanized me.

Meanwhile, we are on very good terms with our mother, I extremely thank her for her great role in my full recovery, especially since she was healed before me. I took a bold step in October this year by bringing together 18 relatives, including my maternal cousins and paternal relatives. It stood as a significant occasion that brought joy to both sides, and they expressed their deep gratitude to me for this initiative. I am determined to restore strong unity among them to the fullest.”

“I’m no longer labelled ‘a child of an interahamwe [genocide perpetrator], I am not disgraced by what my father has done and consequently fail to work, I am no longer enslaved by the history, no longer bound by its chains. As for anyone you among who carries a story like mine, I seize this opportunity to encourage you to take a step and throw this unbearable burden from your head.”

Responses to questions raised by some of the students

Christophe Mbonyingabo is CARSA’s Executive Director. He said “In terms of the question pertaining to ethnics where you have said people used to say the Tutsi are tall, the Hutu are robust and short, and the question ‘What has happened to the Twa?’, I am going to provide you with a response which answers both questions. ”

Those were questions raised by some of the Ruyanza School Complex, since they were furnished with space to ask questions that they harbored after testimonies given by Hagenimana as well as François Nsengiyumva and Bénoit Muhirwa as you can see it in this article.

Here is the response. “There exist three essential conditions which characterize an ethnic, not only here in Rwanda but also anywhere in the world. Those are a language, culture and specific territory. The Rwandese share the same language [Kinyarwanda], culture as our national anthem also specifies it, saying ‘The culture that we share marks us’.

You have understood that they [Tutsi and Hutu] were living together. But the bad leadership [of Rwanda] after the independence embraced discrimination and division, dating back over decades and decades, brought by colonialists who introduced identity cards which specified the so-called ethnics, unlike today when identity cards just state that you are Rwandan.”

He adds “Formerly, Hutu, Twa and Tutsi were inscribed on the cards. A person was provided with an identity card specifying they were a Hutu, or Tutsi or Twa. But a person could also move from one social group to another one; a Hutu could become a Tutsi or a Tutsi could become a Hutu. The bad leadership kept the practice which had proceeded from the colonialists who applied the ‘Divide and Rule principle’.”

In the depths of Rwanda’s painful history, a powerful deception has been woven—one that has altered the course of its people’s lives. Colonial rulers have sought to divide the population, not by genuine differences, but by fabricated distinctions, according to Mbonyingabo. The result was a deep-seated division— he further points out— solidified by falsehoods which were perpetuated by the poor leadership long after the independence, leaving a legacy of discord and violence.

He says “Arriving in Rwanda and lacking a basis for them to divide the Rwandese, the colonialists, they advised themselves ‘Let’s divide them, founded on their social classes and then distribute to them identity cards that separate them, while also advancing other intangible factors [like saying the Tutsi are tall while the Hutu are strong and short].’ That’s why you have also raised the point that you see both tall and short people among people formerly called ‘Tutsi’; which justifies that those claims were groundless.

Those were pure lies brought by the colonialists and the bad leadership— after the independence— who built on these lies and continued formalizing the lies in identity cards, so as to keep power alone. The bad leadership eventually said that the Tutsi are bad people, enemies of the country.”

The following quote sheds light on the uncertainty surrounding the assassination of Rwanda’s former president, where Mbonyingabo emphasizes on how false narratives have been crafted to incite violence and justify horrific actions. “To respond to the other question of the shooting of the plane which was carrying the former President [Juvenal Habyarimana], up to now nobody knows who has shot the plane down. Research has been conducted but it has not yet reached consensus on what we can affirm around the shooting.

Yet what is true is that the plane was downed, and they fabricated the lie that it was brought down by the Tutsi, for them to get a trigger to kill all the Tutsi. They then said ‘We now obtain the reason, the Tutsi have assassinated the president. That is how they mobilized people like François you see here, saying ‘It is these people who have killed the president; stand up [and kill them all].”

According to Musée de l’Holocauste Montréal supports Mbonyingabo’s statement. It says “In the 1930’s, Belgian authorities implemented an official racial division by introducing identity cards that classified individuals as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa.”

The Musée de l’Holocauste Montréal (Montreal Holocaust Museum) is a museum located in Montreal, Canada, dedicated to educating the public about the Holocaust and its devastating impact on Jewish communities and other targeted groups during World War II. It serves as a place of remembrance, reflection, and learning, offering exhibitions, educational programs, and resources about the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime.

Mukagihana works as Kamonyi District’s Itorero and Community Mobilization Officer. Itorero can be translated as the National Civic Education Training Program. She has told the students “Have you seen these people who are before us? Observing them in their faces, do you notice any difference between them? If we take blood from their bodies, will it differ? Are their faces different?”

“I seize from this to tell you that we, Rwandese, are one. Avoid anything which can divide you, since our unity constitutes our strength, though we don’t ignore that there are some parents— whom describe as irresponsible parents— who still harbor the genocide ideology.”

She has explained how they detect the genocide ideology. “Do you know how we discover it? We detect it through some children like you who ask us questions, so that when you probe further, they answer you that they have been told about it by their parents. But, be the solution [to the problem].

As that old man [Muhirwa] has already said it, formerly at school we were told to stand up and they asked ‘Who is a Tutsi?’ and you then stood up and they ticked. ‘Who is a Hutu?’ You stood up and they ticked. Today, the politics of Rwandans’ unity takes precedence. Today at school they tell no students to stand up and ask them ‘Who is a Hutu? Who is a Tutsi?’”

Breaking the chains of history: a global struggle for unity and healing

ReliefWeb constitutes a humanitarian information portal under the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs (OCHA). It contains over 720,000 reports, evaluations, guidelines, and additional resources, and works to provide reliable, up-to-date information on global crises and disasters around the world. On 19 November 2019, ReliefWeb released an article headlined “Reconciliation Must Evolve to Reflect Growing Complexity of Today’s Conflicts, Participants Stress during Day-Long Security Council Open Debate.”

It reads “Hailing reconciliation as a powerful means by which to help societies heal after brutal wars and mass atrocities, speakers emphasized today that the concept must also evolve to tackle increasingly complex modern‑day conflicts — often related to polarization, inequality and growing mistrust of institutions — as the Security Council held its first open debate on the matter in 15 years.

More than 60 speakers from around the globe shared their national experiences with various tribunals, truth commissions, reparations programmes and other reconciliation instruments, highlighting lessons learned. Recounting their roles as mediators, donors, peacekeepers or participants, many emphasized that reconciliation is neither swift nor simple, but remains possible and even highly effective if properly executed.”

In his opening remarks, Secretary‑General António Guterres then underlined “Reconciliation helps to repair fractures caused by an absence of trust between State and people.” He emphasized that successful reconciliation requires both institutions and individuals to acknowledge their role in past crimes and that perpetrators need to muster the courage to face the truth. He, like others, underscored that the international community’s idea of reconciliation must keep pace with the changing nature of conflict.

Hagenimana’s journey from shame and rejection to empowerment mirrors broader struggles faced by individuals and societies around the world as they grapple with the legacies of violence and division. The profound trauma that she endured as the daughter of a genocide perpetrator, coupled with the stigmatization that came from her father’s actions, reflects a personal history bound by the chains of collective suffering.

Just as the officials point out the effects of colonial manipulation— which fabricated false ethnic distinctions to divide people for political gain— Elisabeth’s story underscores the human cost of such divisions—where individuals inherit not only the physical wounds of their ancestors, but also the psychological scars of a fractured society.

The statements of officials like Christophe Mbonyingabo and Mukagihana echo the powerful message that unity is crucial to healing. Their assertion that Rwandans are one, regardless of their historical affiliations, provides a poignant contrast to the lies that once divided them. The hope that Hagenimana and others on the path of unity and reconciliation now embrace is rooted in this unity. She no longer allows her father’s crimes to define her; which shows that the process of reconciliation and healing requires both personal accountability and collective action.

Global conflicts today, as noted by the ReliefWeb report, continue to show the devastating impact of polarization and inequality—issues that transcend national borders and require a rethinking of reconciliation processes. In Rwanda, as in many places, the path to healing has been long and fraught with difficulty.

But as Hagenimana and other people’s journeys (including those featured in our last article mentioned) illustrate it, reconciliation is not just a political or institutional endeavor—it is deeply personal. It requires individuals to confront painful truths, to heal from their wounds, and to move beyond the historical chains that bind them. By facing the painful realities of their past, individuals like Hagenimana can help to dismantle the false narratives that perpetuate division, creating room for a future built on trust, understanding, and unity.

This was a great piece of work which has changed my perspective, thoughts and narratives of what occurred in Rwanda 🇷🇼 in 1994. There’s a high degree of resilience Elizabeth exhibited in her upbringing right from primary school, and I resonate with her coming from a war torn country like Liberia where my childhood was devastated by war. However, I’m so

glad that the country Rwanda has since been transformed and on the road to recovery.

It might take years, but they will get there eventually.

Thanks for the great story.

Prince Flowers – Canada 🇨🇦

Thank you a lot indeed for this uplifting comment.