When we glance at the world around us, it is easy to assume that much of what we use daily constitutes the product of modern invention. Yet many things we treat as contemporary conveniences form, in fact, inheritances from civilizations long gone. Among them features something so ordinary that we scarcely pause to question its origins: the alphabet—the 26 letters in English or French and 24 in Kinyarwanda. The 26 letters from A to Z which shape our words, thoughts, and identities, are not a modern creation at all—they are the outcome of a journey that began thousands of years ago, carried across empires and cultures until they reached us in their present form.

The alphabet has contributed enormously to how the modern world stands today. Its impact goes far beyond just writing; it has molded communication, culture, knowledge, and power. Imagine—today, on 3 September 2025 when we publish this story, we are still employing a writing system invented millennia ago. Isn’t this unusual? Think of it on this very day when, despite years and years passed, humanity is still continuing to rely on a writing system whose roots stretch back thousands of years. Doesn’t that feel like carrying a quiet secret from the ancients? Isn’t it astonishing—and perhaps unsettling—that in an age of innovation, our most basic tool for thought is so ancient?

The maximally noble reason to produce this article is to remind humanity of its shared heritage and interconnectedness through something as simple yet profound as the alphabet. One of the key reasons is to inspire humility—showing that our modern achievements are built upon the wisdom and creativity of those who came before us.

The alphabet’s enduring power

Its power lies in literacy, knowledge diffusion, and cultural connection, among others. The alphabet has permitted universal literacy and learning, preservation and spread of knowledge, global communication, while shaping identities and attitudes and acting as a catalyst for progress.

The alphabet is very simple, compared to other writing systems like cuneiform or Chinese characters. With just a few dozen symbols, anyone can quickly learn to read and write the alphabet. This accessibility has laid the foundation for mass literacy and education across the globe.

The alphabet has preserved and spread knowledge through ancient texts, laws, religious scriptures, and scientific discoveries recorded, copied, and transmitted across generations. The alphabet has made knowledge portable, durable, and shareable—essential for the development of science, philosophy, and literature.

The alphabet has allowed global communication, in that the Latin alphabet, in particular, spread widely through trade, colonization, and technology. Today, it underpins not only languages but also global communication from email addresses to programming languages.

The alphabet has molded identities and cultures, through written languages, based on the alphabet, which have become markers of cultural identity— whether Hebrew for Jewish tradition, Arabic for Islamic civilization, or Latin-based scripts for much of the West. They have shaped national and religious cohesion.

The alphabet has served as catalyst for progress, in the sense that printing presses, books, newspapers, and eventually digital platforms all rely on alphabetic writing. This has rendered it possible to democratize ideas, fuel revolutions, accelerate innovation, and build the interconnected world we live in today. In short, the alphabet is one of humanity’s greatest inventions—it has furnished us with literacy, preserved our history, connected cultures, and powered the rise of science to an unprecented levels, among others.

Origin of the alphabet

To understand this remarkable continuity, we must journey back thousands of years to where it all began. The alphabet as we know it did not appear overnight; it evolved from earlier systems of symbols used to record trade, law, and stories. Scholars point to the Phoenicians, a seafaring people of the eastern Mediterranean Sea during antiquity , as the first to develop a fully phonetic writing system—one where each symbol represented a distinct sound rather than an entire word or concept.

From their shores, this revolutionary system reportedly spread to the Greeks who adapted it and added vowels, and then to the Romans—whose version became the foundation of the Latin alphabet used across much of the modern world. What seems so ordinary today—writing letters on a page—is the product of centuries of innovation, adaptation, and cultural exchange.

Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania is a public university in the United States of America. It has released an undated piece headlined “The Origin of the Alphabet”. It states “The original alphabet was developed by a Semitic people living in or near Egypt. They based it on the idea developed by the Egyptians, but used their own specific symbols. It was quickly adopted by their neighbors and relatives to the east and north, the Canaanites, the Hebrews, and the Phoenicians.

The Phoenicians spread their alphabet to other people of the Near East and Asia Minor, as well as to the Arabs, the Greeks, and the Etruscans, and as far west as present day Spain. The letters and names [ on the below table from this university’s website] on the left are the ones used by the Phoenicians. The letters on the right are possible earlier versions. If you don’t recognize the letters, keep in mind that they have since been reversed (since the Phoenicians wrote from right to left) and often turned on their sides!”

|

‘aleph, the ox, began as the image of an ox’s head. It represents a glottal stop before a vowel. The Greeks, needing vowel symbols, used it for alpha (A). The Romans used it as A. |  |

|

Beth, the house, may have derived from a more rectangular Egyptian alphabetic glyph of a reed shelter (but which stood for the sound h). The Greeks called it beta (B), and it was passed on to the Romans as B. |  |

|

Gimel, the camel, may have originally been the image of a boomerang-like throwing stick. The Greeks called it gamma (Γ). The Etruscans — who had no g sound — used it for the k sound, and passed it on to the Romans as C. They in turn added a short bar to it to make it do double duty as G. |  |

|

Daleth, the door, may have originally been a fish! The Greeks turned it into delta (Δ), and passed it on to the Romans as D. |  |

|

He may have meant window, but originally represented a man, facing us with raised arms, calling out or praying. The Greeks used it for the vowel epsilon (E, “simple E”). The Romans used it as E. |  |

|

Waw, the hook, may originally have represented a mace. The Greeks used one version of waw which looked like our F, which they called digamma, for the number 6. This was used by the Etruscans for v, and they passed it on to the Romans as F. The Greeks had a second version — upsilon (Υ)– which they moved to to the back of their alphabet. The Romans used a version of upsilon for V, which later would be written U as well, then adopted the Greek form as Y. In 7th century England, the W — “double-u” — was created. |  |

|

Zayin may have meant sword or some other kind of weapon. The Greeks used it for zeta (Z). The Romans only adopted it later as Z, and put it at the end of their alphabet. |  |

|

H.eth, the fence, was a “deep throat” (pharyngeal) consonant. The Greeks used it for the vowel eta (H), but the Romans used it for H. |  |

|

Teth may have originally represented a spindle. The Greeks used it for theta (Θ), but the Romans, who did not have the th sound, dropped it. |  |

|

Yodh, the hand, began as a representation of the entire arm. The Greeks used a highly simplified version of it for iota (Ι). The Romans used it as I, and later added a variation for J. |  |

|

Kaph, the hollow or palm of the hand, was adopted by the Greeks for kappa (K) and passed it on to the Romans as K. |  |

|

Lamedh began as a picture of an ox stick or goad. The Greeks used it for lambda (Λ). The Romans turned it into L. |  |

|

Mem, the water, became the Greek mu (M). The Romans kept it as M. |  |

|

Nun, the fish, was originally a snake or eel. The Greeks used it for nu (N), and the Romans for N. |  |

|

Samekh, which also meant fish, is of uncertain origin. It may have originally represented a tent peg or some kind of support. It bears a strong resemblance to the Egyptian djed pillar seen in many sacred carvings. The Greeks used it for xi (Ξ) and a simplified variation of it for chi (X). The Romans kept only the variation as X. |  |

|

‘ayin, the eye, was another “deep throat” consonant. The Greeks used it for omicron (O, “little O”). They developed a variation of it for omega (Ω, “big O”), and put it at the end of their alphabet. The Romans kept the original for O. |  |

|

Pe, the mouth, may have originally been a symbol for a corner. The Greeks used it for pi (Π). The Romans closed up one side and turned it into P. |  |

|

Sade, a sound between s and sh, is of uncertain origin. It may have originally been a symbol for a plant, but later looks more like a fish hook. The Greeks did not use it, although an odd variation does show up as sampi (Ϡ), a symbol for 900. The Etruscans used it in the shape of an M for their sh sound, but the Romans had no need for it. |  |

|

Qoph, the monkey, may have originally represented a knot. It was used for a sound similar to k but further back in the mouth. The Greeks only used it for the number 90 (Ϙ), but the Etruscans and Romans kept it for Q. |  |

|

Resh, the head, was used by the Greeks for rho (P). The Romans added a line to differentiate it from their P and made it R. |  |

|

Shin, the tooth, may have originally represented a bow. Although it was first pronounced sh, the Greeks used it sideways for sigma (Σ). The Romans rounded it to make S. |  |

|

Taw, the mark, was used by the Greeks for tau (T). The Romans used it for T. |  |

The university adds “Until recently, it was believed that these people lived in the Sinai desert and began using their alphabet in the 1700’s bc. In 1998, archeologist John Darnell discovered rock carvings in southern Egypt’s ‘Valley of Horrors’ that push back the origin of the alphabet to the 1900’s bc or even earlier. Details suggest that the inventors were Semitic people working in Egypt, who thereafter passed the idea on to their relatives further east.”

Phoenicia was an ancient civilization situated along a coast of the Mediterranean, in what is today mainly Lebanon and parts of Syria, and northern Israel. It existed roughly between 1500 BCE and 300 BCE. They were exceptional sailors and traders, establishing trade networks across the Mediterranean and even reaching as far as North Africa, Spain, and possibly Britain. Britannica says “Phoenician, person who inhabited one of the city-states of ancient Phoenicia, such as Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, or Berot (modern Beirut), or one of their colonies. Phoenicia, ancient region along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean that corresponds to modern Lebanon, with adjoining parts of modern Syria and Israel. Its location along major trade routes led its inhabitants, called Phoenicians, to become notable merchants, traders, and colonizers in the 1st millennium bce.

By the 2nd millennium bce they had settled in the Levant, North Africa, Anatolia, and Cyprus. They traded wood, cloth, dyes, embroideries, wine, and decorative objects; ivory and wood carving became their specialties, and the work of Phoenician goldsmiths and metalsmiths was well known.” “Their alphabet became the basis of the Greek alphabet,” also highlights Britanncia. The Phoenician alphabet consisted of 22 consonantal letters.

Phoenicia wasn’t a unified nation but a collection of independent city-states, such as Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos, each with its own king and government. World History explains “Phoenicia was never a single political entity but rather a collection of culturally similar cities on the narrow strip of the Levant. Each city had its own independent system of government, which controlled the city and its surrounding territory. Even when the cities acted with the same policies, they did so individually. At certain times one city might be more dominant than another in the region but individual autonomy was not perhaps compromised. Sidon dominated in the 12th and 11th centuries BCE while thereafter Tyre was the most powerful Phoenician city.”

Understanding Phoenicia’s geographic position, extensive trade networks, and cultural influence—as explained above— helps to explain why its alphabet generated such a profound impact on subsequent writing systems. As exceptional merchants and colonizers, the Phoenicians needed a simple, practical system for recording transactions and communications across the Mediterranean; which resulted in the development of their 22-letter consonantal script. By providing this background, we can better explain how the Phoenician alphabet became the foundation for the Greek alphabet and, ultimately, much of the modern alphabet we use today.

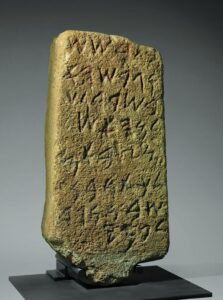

The sandstone stele from Sardinia features a character that closely resembles the modern letter “W” immediately catching the eye of contemporary viewers. However, this “W” in the Phoenician script does not represent the same sound or usage as our modern “W”; it is an early alphabetic symbol with a distinct phonetic value in the Phoenician language. Noticing this character underscores both the continuity and transformation of alphabetic symbols from ancient Phoenicia to the scripts we use today.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) constitutes an encyclopedic art museum in New York City, founded in 1870. In 22 its December 2014 article entitled “Alphabet Origins: From Kipling to Sinai”, it states “Much of what we know about the interconnectivity of the Mediterranean world in the first millennium B.C. relies on archaeological discoveries of the past two centuries. Indeed, behind all of the objects on display in Assyria to Iberia lie modern stories of discovery and recovery. The city of Babylon in southern Iraq, once reduced almost to a figment of modern imagination, was revealed by excavations beginning in the nineteenth century.

The Assyrian empire, once unknown outside the Bible, was brought to light by excavations in northern Iraq beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. And the cities of the Phoenician homeland in modern Lebanon were explored in the mid-nineteenth century and then excavated beginning in the 1920s. Archaeological discovery has also played an important role in our understanding of the origins of the alphabet, which was invented in the early second millennium B.C. and spread across the Mediterranean world in the first millennium B.C.”

The story of the alphabet is both ancient and mysterious, a thread weaving together the origins of writing with the rise of human civilization. At the dawn of the twentieth century, scholars were still piecing together fragments of evidence to explain where our modern alphabet truly came from. “Just over a hundred years ago, at the outset of the twentieth century, little was known about the origin of our modern alphabet. Multiple alphabets, including the Greek and Phoenician alphabets, were used in the first millennium B.C.

Archaeological evidence for the Phoenician alphabet (deciphered as early as the mid-eighteenth century) appears across the Mediterranean, suggesting the widespread presence of Phoenician merchants and colonists. Books written at the turn of the last century, such as Isaac Taylor’s The Alphabet: An Account of the Origin and Development of Letters (1883) and Edward Clodd’s The Story of the Alphabet (1900), speculated about the origin of our modern alphabet and the relationship between the various alphabets.”

While scholars debated the alphabet’s true beginning, writers and storytellers also found inspiration in its mystery. Among them was Rudyard Kipling who in 1902 wove a playful fictional tale of its invention into his Just So Stories. The Met explains “During this time of speculation about the origin of the alphabet, the English novelist and children’s author Rudyard Kipling wrote ‘How the Alphabet was Made’, a fictional account of the alphabet’s invention.

Published in 1902 as part of the Just So Stories, this children’s tale describes how a ‘Primitive’ cave-dwelling Neolithic girl, Taffy, and her father, Tegumai, use various strategies to invent ‘noise pictures.’ Kipling was not a scholar of ancient writing systems or languages, but his story reflects the popularity of the topic of alphabet origins at the beginning of the twentieth century. Soon, far more would be known about how the alphabet was actually invented, and the world in which it originated.”

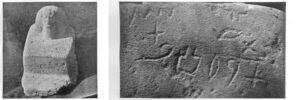

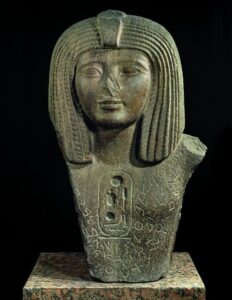

Very few years after Kipling enchanted the world with Just So Stories, another story—this one buried deep in stone—began to unfold. The Met puts “Just two years after the publication of Kipling’s Just So Stories, the English archaeologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie made a discovery in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula that would begin to solve the question of the alphabet’s origin. At Serabit el-Khadim, the site of an Egyptian turquoise mine used extensively during the second millennium B.C., Petrie found numerous inscriptions, both near the mine and at a local temple of the goddess Hathor. Although the majority of the inscriptions were written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, several undecipherable writings were also discovered.

The pictographic signs of these inscriptions were not like those written with the hieroglyphs and could not be interpreted using the ancient Egyptian language. Several scholars, including Petrie himself, suggested that these pictograms might represent some form of alphabetic writing, but it was the English Egyptologist, Sir Alan Henderson Gardiner, who identified the Sinai writings as the hypothesized, but previously unknown, ancestor of the Phoenician (and Greek) alphabet. Unlike previous scholars working on the origins of the alphabet, Gardiner asserted that the West Semitic letter names must have been part and parcel of the invention of the alphabet. The alphabet would have been created by speakers of a West Semitic language, probably the Levantine ancestors of the Phoenicians.”

The search for the alphabet’s earliest traces has led scholars deep into the ancient world where pictographic signs were gradually transformed into the letters we know today. Evidence first pinpointed by Gardiner and later supported by discoveries in Egypt points to Semitic speakers adapting Egyptian scripts as the foundation of the alphabet. “Dated by Gardiner and others to the early second millennium B.C., these pictographic signs are the ancestors of our modern letters.”

“The names of the first two signs (Hebrew ’ālep and bêt; Greek alpha and beta) form the basis of our modern word ‘alphabet’ (Greek alphabētos; Latin alphabetum), and were transmitted, with the rest of the letters, from the Phoenicians to the Greeks and Etruscans, and then to the Romans. While Gardiner’s proposal was debated for decades, the recent discovery of additional alphabetic writings on the cliffs alongside a road through the desert at Wadi el-Hol in Egypt have added credence to his idea that the alphabet was invented in the early part of the second millennium B.C. by Semitic speakers who drew upon Egyptian hieroglyphic (and hieratic) writing.”

Pictographic signs are symbols that directly represent objects, actions, or ideas through pictures (for example, an image of the sun meaning ‘sun’). These are typical of very early writing systems like ancient Sumerian pictographs or Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Alphabet impact

As already suggested, the journey did not stop with the Romans. As Europe entered the Middle Ages, the alphabet turned into the vessel for preserving knowledge in monasteries and libraries, safeguarding religious texts, philosophy, and scientific discoveries. When the printing press emerged in the 15th century, the alphabet suddenly acquired unprecedented power: ideas could be reproduced, shared, and spread widely. What had once been the privilege of scribes became accessible to anyone who could read, laying the groundwork for mass education, scientific advancement, and cultural flourishing.

Across continents, the Latin alphabet continued to travel. It mingled with local languages, adapted to new sounds, and became the script for modern European tongues—and eventually for global communication. Today, whether in emails, books, programming languages, or signage, the letters from A to Z silently connect billions of people across time zones, continents, and cultures. This simple system of symbols, devised millennia ago, underpins the very infrastructure of our digital and intellectual world today.

Yet beyond its practical power, the alphabet carries a symbolic significance: it constitutes a bridge between generations, a shared inheritance that links our thoughts with those of people long gone. Every letter we write, every word we form, is a quiet echo of humanity’s creativity and perseverance across centuries. By tracing these letters back to their ancient origins, we are reminded that progress is rarely sudden—it forms the accumulation of countless insights, efforts, and adaptations over time.

Back to the noblest reason for writing about the alphabet

As already implied in the introduction, the noblest reason is to awaken awareness that our shared letters are a living bridge between past and present, uniting humanity across millennia. This evokes the humility of the current generation toward our ancestors.

The alphabet inspires humility because it reminds us that even our most advanced achievements—including those standing unbelievable— rest upon foundations established millennia ago. Every letter we write, every idea we record, bears the imprint of generations that shaped language, thought, and communication long before us. Recognizing this legacy fosters a sense of reverence and modesty, showing that our modern accomplishments—no matter how extremely groundbreaking—are built upon the wisdom, creativity, and ingenuity of those who preceded us. In acknowledging this continuum, we are reminded that progress is rarely solitary; it constitutes a collective endeavor spanning the breadth of human history.

The second reason is to remind readers that the alphabet has always fostered connection by serving as a bridge across cultures and centuries. It belongs to no single nation or people; rather, it is a shared inheritance transferred and refined through the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, and countless others. Each adaptation, each transformation, reflects the contributions of diverse civilizations, reminding us that communication—and by extension, human connection—is a collective achievement. In using the alphabet today, we participate in a lineage that transcends borders, languages, and epochs, highlighting the power of shared knowledge to connect humanity.

The third reason for writing about the alphabet is to show how it empowers readers, revealing that what appears ordinary is, in fact, extraordinary. At first glance, letters may seem simple, even mundane—but each one carries the weight of centuries of human ingenuity, adaptation, and creativity. By engaging with the alphabet, we are reminded that we participate in something far larger than ourselves: a continuous chain of human progress stretching back through time.

Every word we write, every thought we express, connects us to generations which came before and inspires us to contribute to those who will follow. Recognizing this continuum empowers us to see our own potential, clarifying that even small acts—learning, creating, sharing—are threads in the vast tapestry of human achievement. In this way, the alphabet is not merely a tool; it is a catalyst that illuminates our place within the enduring story of humanity. With this article, we intend to make our readers realize this “alphabet extraordinariness”, and that they themselves are part of a continuous chain of human progress.

While we believe it is unnecessary to dwell on this other aspect and that one can author books and books on it, let’s quickly say that the alphabet helps to preserve memory. It ensures that we never lose sight of the ancient roots of the tools that sustain knowledge, science, and human connection. Each letter, each word, carries echoes of civilizations long past, reminding us that the discoveries, ideas, and systems we rely on today are built upon foundations painstakingly laid by our ancestors. By preserving this memory, the alphabet allows us to honor the continuity of human thought, to learn from the past, and to carry forward the wisdom which molds our present and future. In this way, writing is more than a practical act—it is an ongoing dialogue with history, a safeguard of the collective knowledge that defines humanity.